Work, Wages and Income

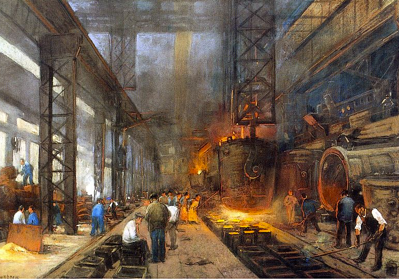

The Industrial Revolution, without a doubt, had many diversified effects on life in British society across classes throughout the nineteenth century. In terms of work, wages, incomes, and the cost of living, much was dependent upon the type of work, the individual employer, and location. While the early period of the Industrial Revolution seemed significantly unfavorable for the working class, the later half of the Industrial Revolution brought increased wages and incomes, indicating that the lives of the working class were on the road to improvement.

As the nineteenth century progressed, less people were working in agricultural positions and were instead employed in manufacturing, mining, transport, and other service industries (Benson 2003, 9). This shift is evidenced in the reduction of agriculture workers from 2.1 million in 1851, to 1.6 million in 1891, representing a shift from 21.7 percent of the workforce to just 10.5 percent, where as employment in manufacturing, mining, and building occupations increased from 4.1 million in 1851 to 6.5 million in 1891 (Benson 2003, 10). Additionally, employment in trade and transport increased from 1.5 million to 3.4 million, domestic and personal workers increased from 1.3 million to 2.0 million, and work in other occupations increased from 0.6 million to 0.8 million, in the respective years (Benson 2003, 10).

Not only was agricultural employment decreasing, the wages of agricultural workers were decreasing as well. The average agricultural laborer earned 10 shillings (s) per week in 1850 and 18s per week in 1880 (Benson 2003, 41). In comparison, cotton spinners earned an average of 23s per week in 1850, later earning 19s per week in 1880 (Benson 2003, 41). Those in the coal mining industry earned 20s per week in 1856, increasing to 21s in 1880 (Benson 2003, 41). On average, earnings were better in industrial employment, even though farm laborers experienced a significant increase in wages. The average working person earned 14s per week, 13s from wages and 1s from self-employment (Benson 2003, 53). Wages increased to 20s total by 1880 with 18s earned in wages and 2s from self-employment (Benson 2003, 53). While wages increased, so did the cost of living (Benson 2003, 55). Regardless, some members of the working class now had some amount of expendable income (Benson 2003, 55).

Though certainly represented in the previous statistics, women in the workforce were employed in slightly different ways than were men. In 1851, there were roughly 2.8 million employed women, accounting for 30 percent of all workers (Bythell 1993, 35). Women were primarily employed in agriculture, domestic service, and in the manufacturing industries, not in coalmines or areas of crafts (Bythell 1993, 36). As an unwritten rule, women earned less than men for the same work, a practice that was aided by “’the bread-winner norm’” and notions of paternal authority and male supremacy (Benson 1993, 59; Bythell 1993, 33). Although earning less than men, it may be assumed that their wages rose in accordance to those of men. Overall, the working class experienced increases of wages and incomes. Those working in industrial occupations, most likely located in cities, experienced more benefit than did those in agriculture, reaffirming that cities had a higher per capita income than did the countryside (Williamson 1994, 340).

- Brittan Duffing