Changing and Growing Cities

Nineteenth century cities in Britain experienced change and growth that coincided with the ongoing industrial revolution. Cities in Britain, on average, were growing at a rate of 2.5% annually in the 1820s (Williamson 1994, 332). The population of Britain increased from roughly seven million to about twenty million at the close of the century (Schofiled 1994, 64). Driving factors behind the increase in general population and growth of cities were immigration and the demographic of young people that made the non-immigrant urban population. As a result, cities typically struggled to keep up to their rates of growth.

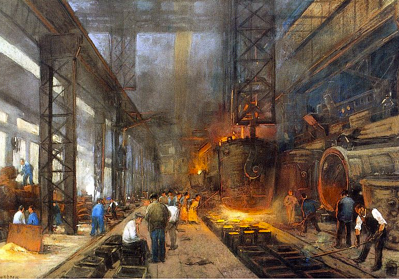

Employment within cities grew at a rate of 1.75% per year between 1821 and 1861 (Williamson 1994, 341). During roughly the same period, wages grew at a rate of 0.91%, even though British manufacturing fell (Williamson 1994, 341, 346). As a result, there existed less of a need for more workers than there would have been in the case that manufacturing was growing. The generally increasing population and growing number of immigrants placed strain on the labor market, as well as housing, resulting in people taking low wage jobs and unfavorable living conditions (Williamson 1994, 347). Competition amongst immigrants and unskilled workers for jobs was strong, allowing capitalists to gain from labor availability.

Furthermore, increased population resulted in shortcomings within the conditions of cities. In his Moral and Physical Condition of the Working Class, James Kay reported that “’houses are noisy, ill ventilated, unprovided with privies…the streets which are narrow, unpaved, and worn into deep ruts, become the common receptacles of mud, refuse, and disgusting ordure…’” further noting that these conditions contributed to the ill health of those living in them (Williamson 1990, 234). Housing was scarce and prices were high; rent accounted for about 20% of ones annual income (Williamson 1990, 235; Williamson 1994, 350). Information collected by the Manchester Statistical Society in the 1830s indicated that Irish immigrants were particularly affected by housing limitations. 11.75% of the Irish population in Manchester was living in cellars, while in Liverpool it was “no less than 15 percent” (Ashton 1968, 110). In other places where there were fewer cases of people living in cellars, the organization stated that it was not that there was less crowding in homes, but that they were cleaner and better furnished (Ashton 1968, 110).

Needless to say, the growing city seemed to immigrants at the time to be a promising place of employment and economic viability. Contrary to their initial beliefs, nineteenth century cities were struggling to incorporate the booming population and increase in the labor force. The image thus reflected by cities was bleak.

- Brittan Duffing