Introduction to Legislation

Throughout much of the nineteenth century, government involvement in the regulation of aspects of the lives of the working class and labor was increasing. Several acts were passed by Parliament that were meant to improve the lives and working conditions of laborers, though they proved difficult to enforce. The majority of the laws that will be highlighted made restrictions to workers behaviors and to their employment, though some regulated more broad aspects of society.

Amongst the most important laws of the nineteenth century were the Poor Laws which sought to regulate relief of the poor. When relief was given in accordance to the New Poor Law of 1834, it was typically made available in the form of employment in workhouses (Smelser, 207). Though this did constitute some relief, it was not always the most beneficial. Some of the poor were simply not physically fit to work. For them, ill health was both a consequence of and contributor to lack of employment.

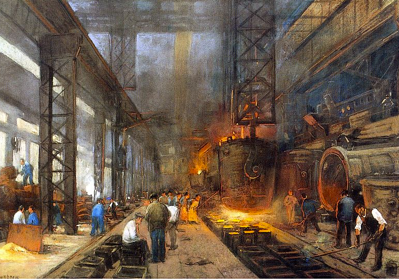

In regards to employment, Factory Laws were passed throughout the century, regulating who could work where and for how long. The employment of children and women was a main concern for acts of this type. An 1802 Factory Act worked to control the conditions of pauper children (Deane, 215). The Factory Act of 1833 restricted the employment of children to an eight-hour day (Smelser, 207). This was later changed to six and a half hours for those under the age of thirteen by the Factory Act of 1844, though the Ten Hours Act of 1847 again changed working hours, limiting women and children to ten-hour days (Smelser, 302). This act was additionally meant to end work on Saturday’s at two in the afternoon and to limit the workweek to sixty hours (Deane, 267).

Laws were also directed towards the regulation of living conditions. The Artisans’ and Labourers’ Dwellings Improvement Act of 1875 and the Housing Of the Working Classes Act of 1890 were meant to improve housing conditions by allowing local authorities to providing housing for rent (Benson, 77). The Public Health Act of 1875 permitted the passing of bye-laws on building standards, called for new streets to be at least one hundred feet in length and 36 feet wide, and for new houses to have “open space at the rear and windows whose area equaled at least ten percent of floor space” (Benson, 77). London sought to control living conditions and health though the 1851 City of London Sewers Act which outlawed living in cellars and the keeping of live cattle in courts (Deane, 219). Furthermore this Act permitted buildings to be condemned and destroyed and also opened the door for the inspection of lodging houses and houses for rent at rates less than 3s 6d per week (Deane, 219).

As evidenced by these examples of legislation, the working class and poor were certainly at the forefront of Parliamentary reform even though many of the laws passed were not as effective as they intended to be. Labor laws were hard to enforce and relied upon the compliance of factory owners. Although laws pertaining to housing were perhaps more effective in that they produced physical changes to the infrastructures of cities, like labor and factory laws, they also proved difficult to enforce.

- Brittan Duffing