**Recursive functions**

# Recursive functions

- The body of a function may contain calls to other functions.

In fact, the body of a function `f` may contain direct calls to

`f` itself.

- A function whose body contains at least a direct call to itself

is said to be _recursive_.

- A function `f` may be _indirectly recursive_ if it does not call

`f` itself, but one of the functions `g` that `f` calls directly

calls `f` (either directly or indirectly).

- When functions `f` and `g` are such that `f` directly

calls `g`, and `g` directly calls `f`, we say that `f` and `g`

are _mutually recursive_.

# An example recursive function

- A canonical example of recursive functions is the `factorial`

function:

```kotlin

fun factorial(n: Int): Int = if (n == 0) 1 else n * factorial(n-1)

```

- There's something to be learned even from this simple example.

# Characteristics of recursive functions

- Every recursive function must have base case(s) where

the function does not call itself.

- All recursive calls have to end up at one of the base cases,

otherwise the program will get into _infinite recursion_.

- Implementation of recursion must be done by the runtime system

of the programming language.

This usually involves a _stack_ of _activation records_.

An activation record is a data structure that keeps track

of the local variables and other house-keeping information

used by an activated function.

- When designing a recursive function, you must not try to

follow the recursion.

Instead, you must use the _magic view of recursion_

where you assume the function works correctly on smaller cases,

and you simply combine the solutions for the smaller cases

to make a solution for the larger case.

# Tower of Hanoi (ToH) puzzle

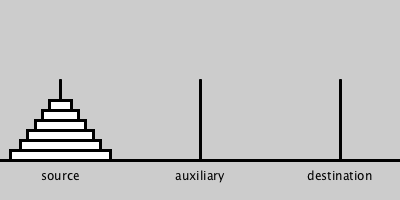

- You are given 3 pegs and n discs of different sizes.

All discs are on the source peg, arranged from top

to bottom in order of size from smallest to largest.

- You are to find a sequence of moves to put all n discs on

the destination peg, using the middle peg as auxillary.

- Each move removes the topmost disc from some peg

and put it on another peg subject to the condition

that a larger disc may not be put on top of a smaller one.

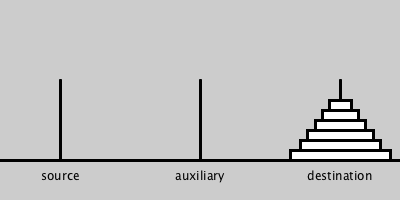

- The first image shows the starting position and

and the second one shows the ending position.

# ToH solution

- This problem can be solved by thinking recursively.

- An optimal solution takes the fewest number of moves possible.

- What is this number as a function of the given number of discs?

- Can you find an optimal solution for every given number of discs?

# ToH solution in Kotlin

- Here is one possible solution to the ToH problem.

```kotlin

/*

* Prints instructions to optimally move n discs from peg `src`

* to peg `des` using peg `aux` as the auxillary peg.

*/

fun hanoi(n: Int, src: Int, aux: Int, des: Int) {

if (n == 1)

println("move top disc from peg $src to peg $des")

else {

hanoi(n-1, src, des, aux)

println("move top disc from peg $src to peg $des")

hanoi(n-1, aux, src, des)

}

}

fun main(args: Array< String >) {

val n = args[0].toInt()

if (n > 0) hanoi(n, 1, 2, 3)

}

```

- **Exercise:** Come up with a more economical solution

(shorter code and/or fewer parameters).

# Recursive graphics

- A recursive graphics is defined in terms of itself.

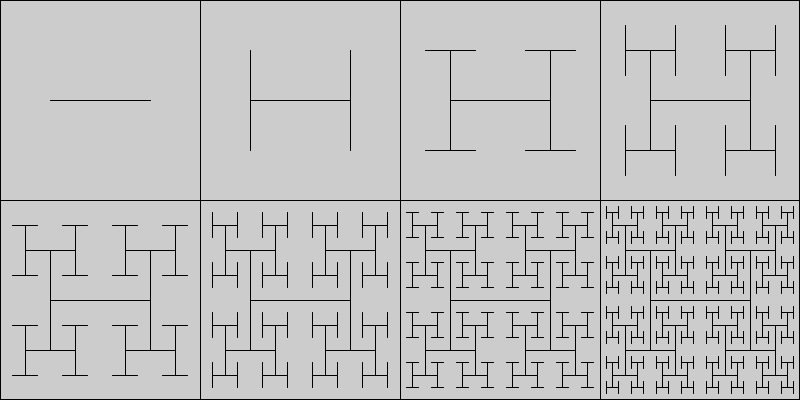

- A good example is the _H-tree_, a self-similar fractal tree

structure with applications in VLSI design and microwave

engineering. The picture below shows the H-trees of

level 1 through 8. Can you describe how the level-$n$ H-tree

is constructed from the level-$(n-1)$ H-tree?

# Drawing the even-level H-Trees

- This Kotlin code draws the even-level H-Trees.

```kotlin

import processing.core.PApplet

fun main() {

PApplet.main("EhtreeSketch");

}

class EhtreeSketch : PApplet() {

var level = 0

override fun settings() {

//size(640, 640)

fullScreen()

noLoop()

}

override fun draw() {

background(250)

ehtree(width/2F, height/2F, width.toFloat(), height.toFloat(), ++level)

level %= 7

}

override fun keyPressed() {

redraw()

}

/*

* Draw a level-2n Htree in the rectangle of width `width`

* and height `height` centered at point (x, y).

*/

fun ehtree(x: Float, y: Float, w: Float, h: Float, n: Int) {

if (n < 1) return

val x0 = x - w / 4F

val x1 = x + w / 4F

val y0 = y - h / 4F

val y1 = y + h / 4F

line(x0, y, x1, y)

line(x0, y0, x0, y1)

line(x1, y0, x1, y1)

ehtree(x0, y0, w / 2F, h / 2F, n - 1)

ehtree(x0, y1, w / 2F, h / 2F, n - 1)

ehtree(x1, y0, w / 2F, h / 2F, n - 1)

ehtree(x1, y1, w / 2F, h / 2F, n - 1)

}

}

```

# Exercise on drawing the H-Trees

- Write a Kotlin program `Htree.kt` using the processing library

that draws a level-`n` Htree when a positive integer argument

`n` is given.

- **Hint:** Imitate the code for drawing the even-level H-Trees

and use mutual recursion.

# Sierpinski triangle

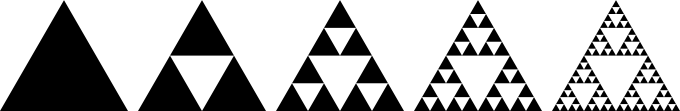

- Another example of recursive graphics is the _Sierpinski Triangle_.

- Here is a picture of the Sierpinski triangle of levels 1, 2, 3, 4,

and 5, respectively.

- Can you describe how to construct the level-$n$ Sierpinski triangle

from the level-$(n-1)$ Sierpinski triangle?

- **Exercise:** Write a Kotlin program using the processing library

to draw the Sierpinski triangle whose level, side length, and

lower left corner are given as parameter. You may assume the triangle

is oriented like in the example picture, with its base parallel

to the x-axis.

# The cost of recursion

- As mentioned previously, the runtime system of a programming language

must provide support for recursive function calls in terms of the

stack of activation records.

- A recursive function while executing can potentially be using an

enormous amount of memory for the activation records of

currently-activated-but-not-yet-finished functions.

- On one hand, a recursive function can cause the so-called

_stack overflow_---a condition in which all the stack memory

the JVM has allocated for your running program is exhausted,

causing your program to abort.

On the other hand, recursive functions can be a direct, clear,

and succinct way to express an algorithm.

So it would be nice if we can write recursive functions that

do not use stack space too heavily.

It turns out this is possible in some cases.

# Tail recursion

- _A recursive function that returns the result of the recursive call

as the result for the caller immediately upon completion of the

recursive call_ is said to be _tail recursive_.

- For example, this version of `factorial`

(to be called with `factorial(n, 1)` when computing $n!$)

is tail-recursive

```kotlin

fun factorial(n: Int, acc: Int): Int =

if (n == 0) acc else factorial(n-1, acc*n)

```

because after the called function `factorial(n-1, acc*n)`

returns, the caller function immediately returns with

that result.

- The original version here

```kotlin

fun factorial(n: Int): Int = if (n == 0) 1 else n * factorial(n-1)

```

is not tail-recursive because after the called function

`factorial(n-1)` returns, the caller function has to

multiply that returned result by `n` before returning

with the new result.

# Tail call optimization

- It turns out the Kotlin compiler knows of a way to transform a

tail-recursive function call into a loop.

- This is great since loops do not consume as much stack memory

as recursion.

- However, you have to tell the compiler to activate this optimization

feature. All you have to do is to put the keyword

_tailrec_ in front of the keyword _fun_ at program definition,

like this:

```kotlin

tailrec fun factorial(n: Int, acc: Int): Int =

if (n == 0) acc else factorial(n-1, acc*n)

```

_---San Skulrattanakulchai_